Back in November 2017, I reviewed a little app called You Need a Budget (YNAB). I like to follow up on posts like this. Time is the crucial ingredient for us ADHDers. It doesn’t take much to convince us a new tool or strategy is a silver bullet.

However, I’m old enough in ADHD years to know those silver bullets eventually lose their shine. Any new success is just “for now” until proven otherwise.

YNAB has stood the test of time. Over three years later, I’m still using it. I still think it’s fantastic for people with ADHD. And I want to talk about why1.

ADHD makes money management difficult

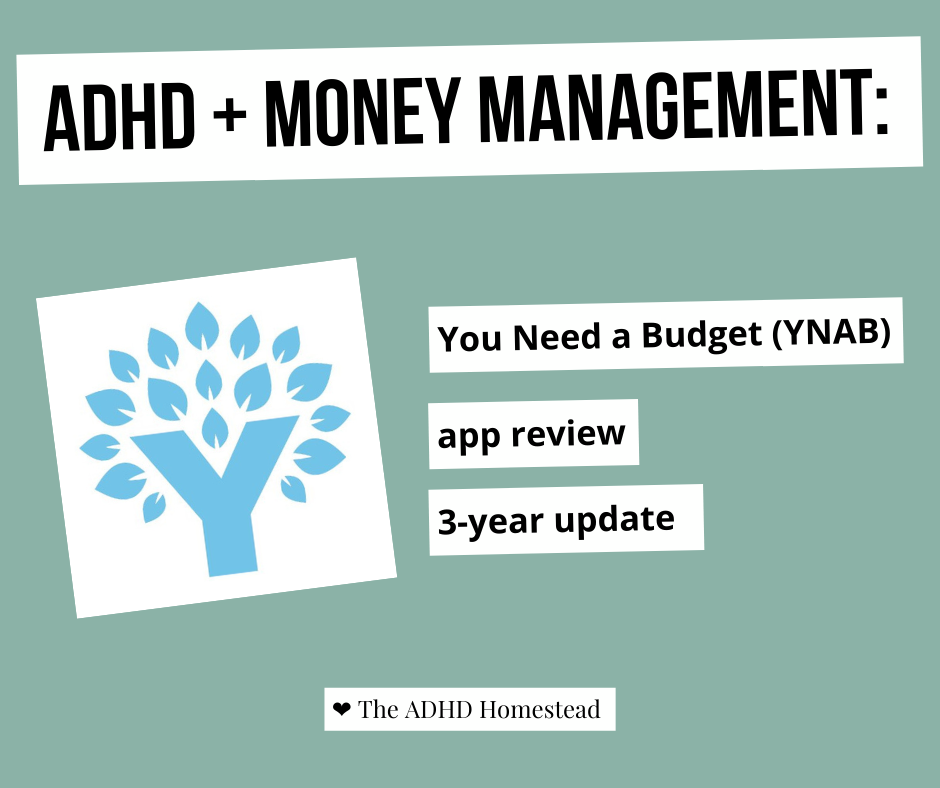

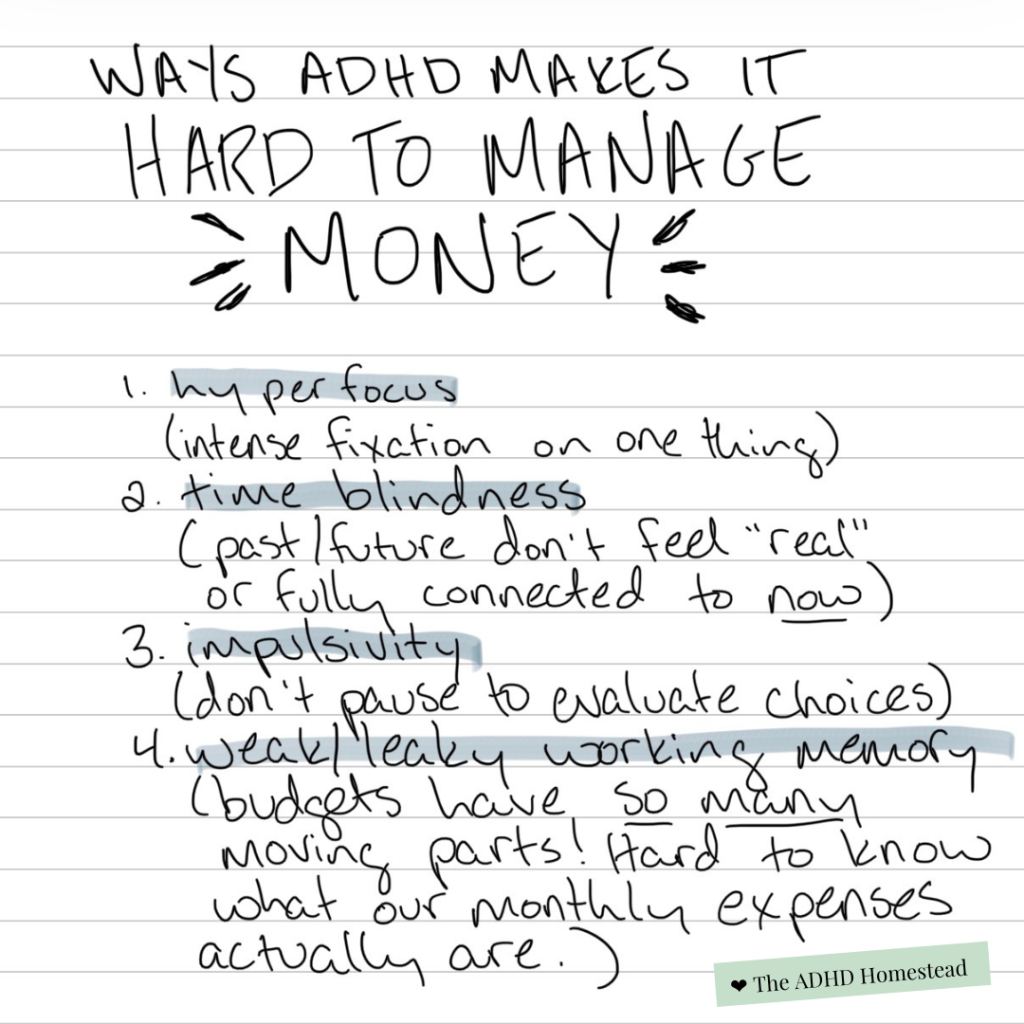

First of all, unless money is one of your hyperfocus sweet spots, ADHD’s time perception and working memory issues will probably make budgeting a challenge.

The brain’s working memory allows us to hold and manipulate more than one thing in our heads at once. Many ADHDers suffer from a weak, or “leaky,” working memory2. For every consideration we add when trying to think through a problem, another seems to slip away.

This makes it hard to conceptualize our financial situation and get a grasp on all its moving parts. Sometimes we have to look at one number, like our bank account balance or the amount of our next paycheck, and figure out if it’s enough to cover this month’s expenses. Those expenses are often a long and varied list. With so many variables, our financial lives can feel full of surprises.

Add to that our impaired time perception — often called time blindness — and associated problems with hyperfocus and impulse control. It’s no exaggeration to say the past and future often feel unreal to us. We struggle to connect our current situation to our past actions, or to use our decisions now to shape the future we want later. This can leave us wishing our financial outlook was different, yet unable to make those desires a reality.

Low impulse control and hyperfocus can also sabotage our best intentions. When we fixate on something, when it becomes the object of our hyperfocus, it swells to consume our entire perception. Time blindness becomes even more pronounced. This plays into our struggles with impulse control: we fail to pause, consider the long-term consequences, and ask ourselves if this is truly what we want.

Where I started (before YNAB)

This perfect storm of factors can — and does — lead to devastating financial stress for many ADHDers. However, I thought I was doing okay when I started using YNAB to manage our household budget. We didn’t have a budget per se, but we had enough money to pay for what we needed, and I had benefited from a sound financial education from my family.

My blue-collar family’s aversion to both extravagance and debt taught me to base purchasing decisions on my bank account, not my perceived needs and desires. Even as a teenager, I chose a minimum balance I would treat as zero in my savings account: a number I would not go below, so I had enough money to cover emergencies.

As I got older, possible emergencies expanded beyond the likelihood of my eighteen-year-old car breaking down. I started hearing advice like, “always keep three months’ living expenses in the bank.”

I had no idea how much three months’ living expenses actually was, but I increased my minimum comfortable balance — my buffer — in my savings account and hoped I’d guessed correctly. For the most part, this worked out.

Where I am now (after several years of YNAB)

I now realize my poor working memory probably inspired my arbitrary “emergency buffer” method of budgeting. I really struggled to tally up all our expenses. No matter how hard I tried, I always missed or forgot something.

YNAB’s “give every dollar a job” ethos was a total game-changer. The app prompts you to assign dollars to your budget as soon as they come in. Once this month’s budget is satisfied, you can begin filling out next month’s. For tricky categories like household supplies or even alcohol, I let the app suggest a budget based on my actual spending habits. For the first time in my life, I could see how many weeks’ or months’ living expenses I actually had in the bank.

Also for the first time, I stopped feeling like I needed to keep a separate pot of money set aside as an “emergency buffer.” My budget in YNAB was my emergency buffer. As it turns out, my “emergency buffer” was really just a buffer against my lack of a budget.

The biggest surprise for me has been, I stopped paying attention to my bank account balances! Because I’ve assigned jobs to every dollar I have via YNAB, I don’t have to worry and check if the number is getting too low. My financial situation has become completely predictable. No more surprises! Or if there are surprises, I can easily figure out how to absorb them.

An added bonus: cushioning against unexpected change

2020 was filled with nothing if not surprises for us. We started the year anticipating a job change for my husband. Because he was also changing industries, we expected this to come with at least a little pay cut.

YNAB helped me in two ways here. First of all, I could know immediately how many months’ expenses we could cover even if we completely stopped earning money tomorrow. This gave me the confidence to tell my husband, do what you want. We’ll figure it out.

I also had a sandbox to help me figure out how large a pay cut we could absorb without having to change our lifestyle. YNAB offers several reporting tools to help you get a picture of your expenses over time. If we needed to cut, I could look down the list and identify places to reduce expenses, as well as fixed expenses we had to pay no matter what.

Little did we know, the new job was hardly the biggest change on the horizon. The pandemic affected everyone’s finances. I was so thankful to have YNAB to help me figure out where our expenses had decreased (e.g. gas and tolls), and distribute those decreases to cover increased costs elsewhere. I also took comfort knowing how many months’ expenses we currently had covered, and how much wiggle room we might have if one or both of us got sick and had to face dramatic shifts in income and expenses.

All in all, YNAB has increased my confidence in our ability to adapt gracefully to change and handle surprises with far less stress.

YNAB is almost tailor-made for ADHD

I credit this to YNAB’s focus on exactly the areas where ADHDers struggle most. General advice like “save up a few months’ living expenses” doesn’t work for us. We often find ourselves with too little cash, but no idea how we could possibly afford to save more.

YNAB takes all the burden off our working memory. It helps us figure out exactly how to reduce spending, increase savings, and adjust to changes in our financial situation. I especially appreciate how YNAB only allows me to budget money I actually have. Every dollar in my bank account already has an assigned purpose. Everything is concrete, nothing is abstract.

This also tempers that ADHD impulsivity by leaving a zero balance for unplanned nonsense. The default setup includes a category called “stuff I forgot to budget for,” but those funds, like everything else, are limited to what you can actually afford to put in there. This makes the impact of impulse buys both immediate and tangible. I, for one, am much less likely to overspend on this week’s fixation if it means moving money away from something else.

Overall, YNAB brings money management out of the abstract and removed — a huge danger zone for ADHDers — and into the present and concrete. I was impressed when I first gave it a whirl in 2017, and I’m only more so now, in 2021. YNAB has seen our ADHD family through an international vacation, transition from private preschool to public elementary school, a job change, and a pandemic. All have impacted our finances, and I’ve been so thankful for a tool to help me manage the details with calm and certainty.

Footnotes

1: Full disclosure: though this is not an ad and I’m not an affiliate or sponsor of YNAB, I do use referral links in this post. YNAB is a subscription-based app, and they advertise an opportunity for all users to earn one free month for every person they refer to the service. It seemed silly not to use my referral link here, but the existence of the referral program (again, available to all users of the app) in no way informed the content or existence of my posts. For more information about my general approach to ads and sponsored content (i.e. why I don’t really do either), see my Full Disclosure Policy.

2: This is summed up well on page 50 of Gina Pera’s book, Is It You, Me, or Adult A.D.D.? Jeff Copper also discusses ADHD working memory issues in an interview with Dr. Russell Barkley on his Attention Talk Video YouTube channel.

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!