Many ADHDers have a reputation for starting more projects than we finish. This erodes our confidence and it creates tension in our households. After so many failed projects, others stop trusting us.

We also stop trusting ourselves. It’s hard to get excited about a new project — or find motivation to get started at all — when we expect it to bring us shame. Even when we do manage to get motivated, one offhand comment can take the wind out of our sails completely.

This happened to me when I told my husband my big plan to make over our backyard. I’d spent over a decade maintaining the yard and gardens we inherited from the previous owner. I wanted it to reflect my values and desires for a change. But my initial sketches and ideas garnered skepticism from my husband.

The most positive feedback he could muster was, “It just seems like a lot.”

That stung.

At the same time, I got it. Other big, destructive home improvement projects had sat half-done for months. Years, even. The time I demolished all the walls in our spare bedroom and left it that way for over a year1 went unmentioned in this conversation, but surely not unforgotten.

So I got to thinking: how can I prove everyone, including myself, wrong on this? How can I get what I want without turning our backyard into a neighborhood embarrassment?

Then I realized: it wasn’t just this project. My husband, always the engineer, has a sour attitude about any big project. Anything I present as one monolithic endeavor where everything happens at once, he sees as bad engineering.

If I wanted his support, I needed a well-engineered project.

A well-engineered project can be broken into pieces that don’t depend on each other.

By day (and by night too, if we’re being honest) my husband writes computer software. One of the most important best practices in software engineering is what’s called separation of concerns.Each part of your program should handle only a single, easily-summarized responsibility. It should also be “shy”2 and keep its internal workings to itself. An app’s many components may cooperate to make the program work, but they stay out of each other’s business while they do it.

This achieves a similar purpose to inserting barriers and gaps between sections of a domino fall. A catastrophic failure or error in one area stays contained. It can’t damage the rest. You can also rework individual sections without fear of unintended consequences down the line. Strict compartmentalization — separation of concerns — makes the whole thing easier to work on.

ADHDers would benefit from thinking of all our big projects this way.

ADHD necessitates well-engineered projects.

My backyard overhaul sounded good in theory, but my husband was right: my plan required too much work all at once. I wanted to dig up all the turf grass and the gardens in one fell swoop, then construct a series of raised beds and flagstone pathways. At the same time, I’d build a pergola hammock stand with container gardens at either end. In other words, I’d destroy everything to give myself a clean slate, then build the garden of my dreams.

Except my stamina would run out before I saw any real rewards. I’d get demoralized and overwhelmed, then abandon the project at the very moment the backyard looked its worst. I may hate to admit it, but experience has taught me this much about myself.

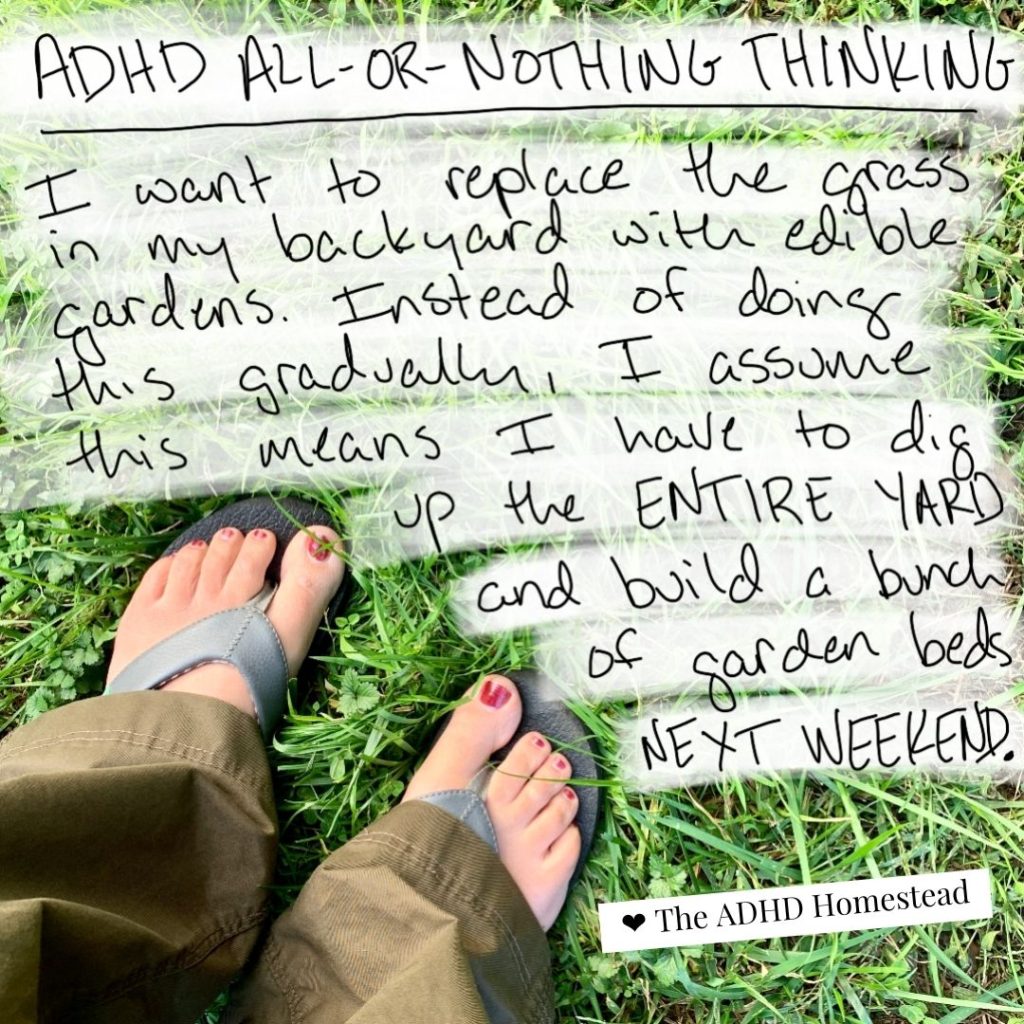

At the same time, I couldn’t give up my backyard dreams entirely. I’d be too disappointed. Plus, my heart was in the right place, if not my mind. Turf grass is a poor use of my backyard resources. I just got tripped up thinking that meant I should tear it all out tomorrow (hello, all-or-nothing thinking).

I needed to split my big idea into smaller, self-contained projects. This would eventually — not this coming weekend, but eventually — lead me to the result I wanted without getting me in over my head.

The ability to break a huge project into smaller parts is a helpful skill for anyone. ADHD makes it a necessity. I’ll avoid the term deficits here, but ADHD gives our brains a few unique vulnerabilities. We ignore them at our own peril — especially when starting a big project.

We have weak working memory.

Topping the list of project saboteurs is our working memory.

Our brain’s working memory allows us to keep more than one thing in our head at once3. Many ADHDers have an especially weak, or “leaky,” working memory.

We can grasp the 10,000-foot view of what needs to happen, but our brains can’t consider all the steps and requirements at once. As we add those pieces to our working memory, others fall out, obscuring the magnitude of what lies ahead. If our enthusiasm for the idea of our project runs away with us, we’ll jump in without a solid plan.

Eventually we get into the thick of it and we have to reckon with the true scope of the project. That opens the floodgates. We max out our cognitive limits, get overwhelmed, and want to quit.

There are strategies to get around this, including breaking projects into smaller pieces than we think we should need to. Our working memory is what it is. We need to give it extra support. In return, our brain will do more of what it does best: cooking up our schemes, ideas, and plans.

We have trouble working long and hard without reward.

ADHD makes us vulnerable to hyperfocusing on and even becoming addicted to activities that offer frequent dopamine-stimulating rewards4. Think playing video games, eating salty snacks, watching YouTube videos, and scrolling social media feeds. I’ve even experienced it with sewing! We can’t pull ourselves away without eating one last pretzel, watching one last video, sewing up one more raw edge (and then one more after that).

Contrast this with a project that isn’t done until everything is done. A project that requires a lot of hard work, perhaps months of hard work, before our brain’s reward centers really light up.

It sounds great in theory — what admirable work ethic! — but in practice ADHDers often lose steam and become unable to continue. People around us say things like “you just have to push through it,” “you quit everything as soon as it stops being fun,” and “I can’t believe the yard is still all torn up — it’s so embarrassing!”

Despite all this shame, and despite being unable to explain our behavior even to ourselves, we’re stuck behind a force field and unable to make progress.

We need to separate projects into smaller jobs that give us satisfying rewards throughout. Not only will this give our brains a dopamine boost and leave us wanting more, small successes build confidence. When we feel more competent, we stand a better chance against overwhelm and paralysis.

We don’t know how long it takes to accomplish a task.

ADHD’s time blindness affects almost everything we do — including project planning.

I have trouble estimating how long my morning routine, which I do every single day, will take to complete. And yet I will merrily go about planning a huge project using phrases like “in October, I’ll dig up the yard and build those garden beds.”

We have two problems here: first, I have no idea how long any of this will take. I might plan to do a portion of this work “next Saturday” without knowing if I’ve laid out a few hours’ or a few days’ worth of effort.

Time-blind ADHDers also struggle to estimate much time we have available. It’s easy to think, “I can work on this next Saturday.” It’s harder to express that as a concrete number of hours. Even if we remember to look at our calendar and account for scheduled obligations, the calendar doesn’t tell the whole story. What about the time it takes to prepare for a meeting, or take care of dinner, or unload the car and put away groceries after a shopping trip? Our calendar may say we have “all day,” but few adults really have “all day” to work on a single task — at least not without consequence.

This is bad enough for small tasks, let alone a big project that feels impossible to stop in the middle. We often find ourselves in a dilemma: do we leave the project in an unacceptable state, or do we steal time we’ve promised to family, friends, or other work?

We can get derailed easily by setbacks.

All these factors converge to make ADHDers extra vulnerable to setbacks. This is doubly true for rigid, all-or-nothing thinkers like me. We come up with one concept for how this big project has to work. That means one wrench in the works can bring everything crashing down.

Setbacks are part of the process. Maybe we get sick, or a kid gets sick, or the roof leaks, or a part is out of stock, or we realize the work we wanted to start this weekend actually requires a permit from the city. Big or small, every project has its snags.

When those snags happen, we call upon our working memory to scoop up our project’s moving parts and rearrange them. We also rely on working memory to figure out what needs to be rearranged in the first place. Which moving parts are even affected by this setback, and how?

After that, we have to estimate how the setback affects our overall timeline. Do we need to adjust deadlines? Reschedule a contractor? Put another project on hold so we can catch up on this one? How much time do we have to devote to this over the next week? Month?

All the while, our anticipated reward — tangible progress — is snatched from our grasp and delayed. ADHDers often experience things as either Now or Not Now. This can make a small delay feel just as demoralizing as putting the project off forever.

Before we know it, a minor setback feels so overwhelming, we give up on the project and walk away — even if we leave behind a mess.

For the same reason our brains need small, smartly-compartmentalized projects, we really struggle to compartmentalize our projects.

Clearly, we ADHDers need to break big projects into manageable pieces and stop biting off more than we can chew. Right?

Sure.

I’ve seen that advice more times than I can count, and it’s really not advice at all. It’s a statement of fact — a fact most of us know already because we’ve been hearing it since before we can remember.

The problem isn’t knowing what we need to do, but knowing how to do it. Like many life skills, others often describe this breaking-projects-into-manageable-chunks thing as innate, obvious, or just plain common sense. Something that should come naturally.

Except it doesn’t come naturally for everyone.

This post is the first in a series where I’ll look at how projects get broken down. I’ll use my yard as an example because it’s what’s in front of me. I’ll go through how to separate a project into smaller components and ensure a setback for one won’t grow into a setback for all.

We don’t have to stay stuck in a cycle of unfinished (or unstarted) projects. However, the last thing we need is to hear the same old “just break it down into smaller pieces” line again. I’m looking forward to digging into the nitty-gritty. Shoot me your questions in the comments below!

Footnotes:

1: I tell the full story of this room, dubbed the Lost Room, in my book Order from Chaos. It actually gets “lost” twice, which is really something.

2: This note is just for the nerds: I got the “shy” thing from the book The Pragmatic Programmer by Andrew Hunt and Dave Thomas. If you want to know more about the software engineering analogies I’ve tried to tone down in this series of posts, check out that book as well as Clean Code by Robert Cecil Martin.

3: For more on working memory and ADHD, see Russell Barkley’s Taking Charge of Adult ADHD (p. 72-81) or Gina Pera’s Is It You, Me, or Adult A.D.D.? (p. 50). Consider this from Pera: “[Working memory] is our ability to hold information in our minds and use it to guide our actions. With strong working memory, our actions stay anchored to the past (where goals are set) and connected to the future (where goals are met).” I’ve learned I can’t trust my working memory to deliver this strength. I need to support it by working things out on paper and in sections.

4: This is because ADHD disrupts our brains’ dopamine pathways. Our brains are often hungrier for those little dopamine hits than neurotypical folks’, which makes us more vulnerable to things that manipulate those dopamine pathways, including drugs, alcohol, and social media algorithms.

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!