Every once in a while a gentle reader shoots me a comment or an email about my use of the term time blindness. I once saw my work reshared with a content warning re: my use of the term. They explained time blindness was a more commonplace and accepted descriptor for ADHDers’ time perception impairments when I published my article (roughly two years prior).

Some folks in the ADHD and disability advocacy communities have come to see time blindness as ableist language. Many consider it harmful to use the word “blind” to describe anything other than visual impairment.

I agree in many cases. As Lydia X.Z. Brown explains in a very handy post on Autistic Hoya, “blind” is often used as a metaphor to describe people who are willfully ignorant, overcome by prejudice, or deliberating ignoring a crucial point. This reminds me of terms describing intellectual disabilities which have been co-opted as insults. Not great.

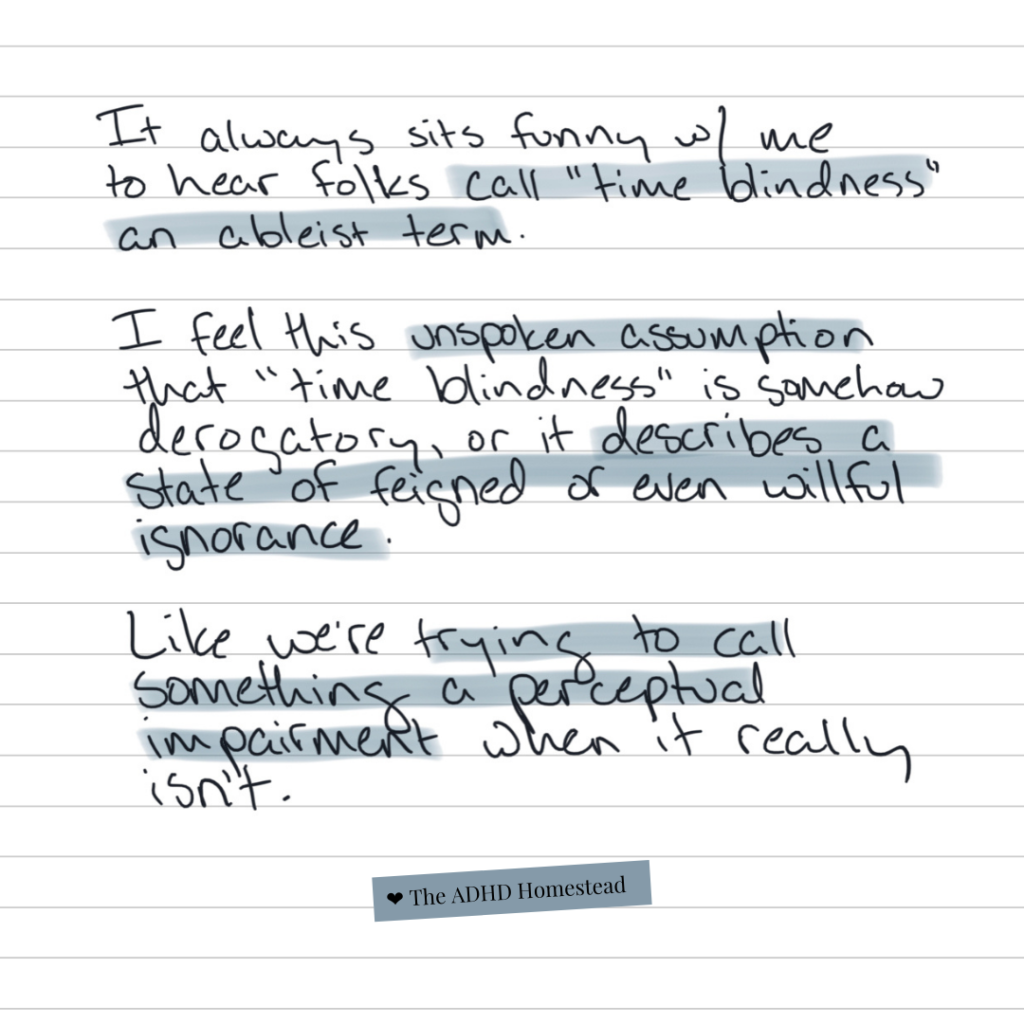

But something about time blindness as an ableist term never sat right with me. Today I’m finally sitting down to articulate why.

For starters: where does the term time blindness come from?

ADHD researcher Dr. Russell Barkley appears to have coined the term time blindness in a 1997 paper about self-regulation and time perception in people with ADHD1. He has also called this phenomenon temporal myopia. In other words, literal near-sightedness to time. He explained the concept well in a talk for the 2009 CADDAC conference, titled ADHD is Time Blindness.

Since then, the professional community has adopted time blindness to describe ADHDers’ time perception challenges.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic obliterated the general population’s time-perception footholds. A surprising number of mainstream media outlets ran articles with time blindness in the headline. I still don’t know how I feel about this. In some ways, it’s great to increase awareness. In others, much of the conversation lands similar to the perennial favorite, “we’re all a little ADHD sometimes.” The pandemic may have created acute symptoms for many people, but that doesn’t mean they understand what it means to live our whole lives this way.

This makes time blindness, much like ADHD itself, a bit of a gray area. The term can be misused and overused by the general population. This behavior ventures into ableist territory similar to language like “I’m feeling so bipolar lately” or “he’s schizo.” But context matters. Bipolar isn’t a derogatory term, it’s a diagnosis. Only when we use these terms colloquially, as (often negative) metaphors, do they become harmful.

What’s the intent of the time blindness metaphor?

Barkley’s original use of “blindness” to refer to time perception was a metaphor in a certain sense, but hardly a derogatory one. He has consistently used the term to help educate the public about how we experience time. This language combats ignorance and stigma around ADHD behaviors.

As I point out in my popular post on ADHD time perception, it’s a particularly harmful aspect of adult ADHD. Time is so much more than productivity and Western cultural norms. It undergirds our ability to maintain healthy relationships and regulate our emotions.

Describing these perceptual challenges as time blindness helps drive home an important point about intent. Rather than irresponsibility and lack of consideration for others, our self-regulation challenges stem from a fundamental inability to perceive time accurately. As Barkley puts it, temporal myopia prevents clear perception of time outside the present.

How I use visual impairment analogies in my writing.

Since I published it in 2018, my post How it really feels to be time-blind with ADHD has consistently remained my most popular. In it I draw an analogy between time blindness and color blindness.

An excerpt:

It’s one thing to know a fact in your brain: this flower garden is full of rich, beautiful shades of red and green. I need to make sure I’m on time for this meeting. It’s quite another to experience it, at a sensory level…You wouldn’t assume a colorblind person simply doesn’t care enough about distinguishing red from green. Neither should you assume a person with ADHD doesn’t care enough to manage time properly.

How it really feels to be time-blind with ADHD, April 11, 2018

The popularity of this post — in March 2021, the eve of its third birthday, nearly forty-five thousand readers found their way to it — tells me it strikes a chord. The comments reflect a wide range of reactions, from extreme gratitude to cantankerous skepticism. I’ve revised a few times over the years, partly in response to the latter. I want to be crystal clear: I may give tough talk to my fellow ADHDers sometimes, but I support them. I get it. My writing isn’t for everyone and I want it to challenge the reader occasionally. At the same time, I don’t want my tone or content to feel outright hurtful.

I’ve stood by my color blindness analogy. It’s the best way I’ve found to undermine ADHD stigma and illustrate the innateness of our limited time perception. Others have made similar comparisons between ADHD medication and medication for less-controversial medical conditions like diabetes or atrial fibrillation. When an aspect of our physiology interferes with our quality of life — even threatens to shorten our lifespan — and a daily medication regimen exists to counter these negative effects, there’s no shame in taking it. These are not things we control, and they don’t reflect our character or commitment.

I also — and here’s the tough talk — appreciate the responsibility implied by the color blindness analogy, as articulated here:

Colorblindness doesn’t give anyone license to ignore traffic signals. It also doesn’t make it okay to demand someone sit in the passenger seat and call out the color of the signal for every ride. Likewise, we ADHDers aren’t doomed to go through life hurting people and letting them down every day, nor should we put the burden of responsibility for our time blindness on others.

How it really feels to be time-blind with ADHD, April 11, 2018

While we don’t choose our perceptual impairments, we are still responsible for them. I don’t say this to dismiss ADHDers’ (or color blind folks’) struggles. Rather, I offer both hope and accountability: we can learn to live and work with our perceptual impairments. Accepting them fully allows us to find accommodations and live fuller lives.

What does it mean to suggest ableism in time blindness?

Returning to Autistic Hoya’s massive list of ableist language, what are the implications of claiming “blindness” has been used in an ableist way here? Brown provides the following suggested alternatives: “willfully ignorant, deliberately ignoring, turning their back on, overcome by prejudice, doubly anonymous [in the case of research studies], had every reason to know, feigned ignorance.”

Every single suggestion in that list sends a clear message about intent: this person could’ve done differently. Instead, they chose to remain ignorant. They closed themselves off to other perspectives. Even in the relatively innocuous example of “double-blind” studies, the terminology reflects choice and intention.

When we talk about time blindness, we are not being flip. We are not being derogatory. We are not describing people who “turn a blind eye to” the clock or “had every reason to know” they did not have time for one more thing before leaving to pick the kids up from school. Rather, we’re saying, we understand the words you use to describe this in theory, but in practice, we can’t perceive it the way you’re describing.

The difference is striking.

I’m left to wonder: what aspect of the term time blindness do people consider ableist? And does this reflect a lingering assumption or bias? A suspicion that maybe this so-called blindness to time isn’t quite as baked-in as we claim, and what we call impairment may be hidden ignorance after all.

Footnotes

1: Barkley, R. A. (1997). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, self-regulation, and time: toward a more comprehensive theory. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics.

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!