This is the first in a series of posts about my journey from ADHD-oblivious, to ADHD-curious, to where I am today. See the full series here.

I could’ve gotten an ADHD diagnosis in high school. Maybe even sooner. I could’ve avoided years of stress, anxiety, shame, and overwhelming emotional highs and lows. Instead of wondering why everyone else seemed to live by a rulebook I couldn’t see, I could’ve had a toolbox to help me navigate my life and relationships.

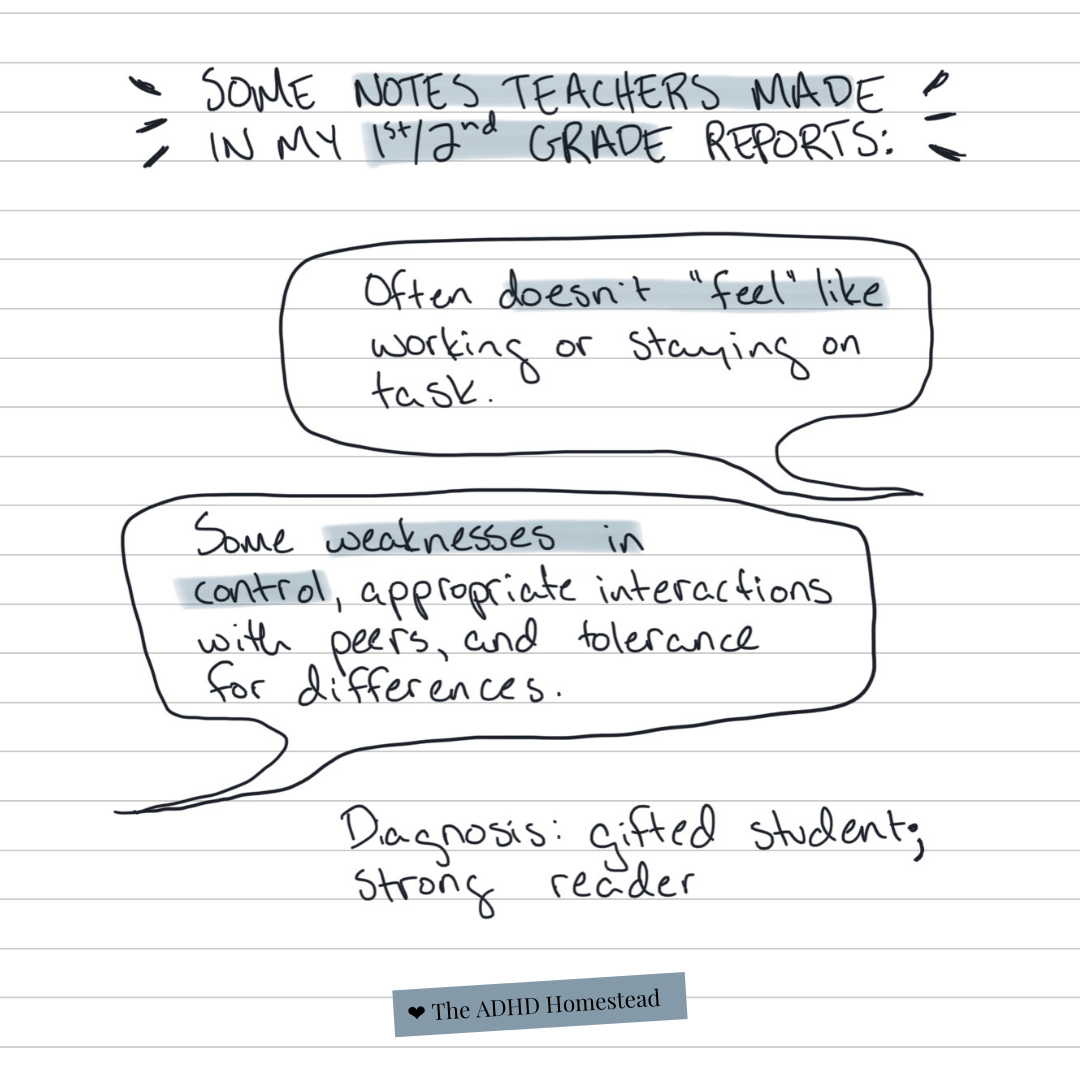

The ADHD red flags arrived on my report cards in first grade.

Unfortunately, no one recognized them. Not even the educators who wrote comments like, “[Jaclyn often] doesn’t ‘feel’ like working and staying on task.”

Popular belief and current diagnostic criteria define three ADHD presentations: hyperactive/impulsive, inattentive, or a combination of the two. I personally believe we’re all combined type. ADHD is ADHD. However, there’s a reason I got missed — and lots of kids continue to get missed thirty years later.

ADHD looks different in everyone. Our temperament, culture, and family environment all affect how it manifests. So does our access to privilege and resources. Where we come from, where we live, all this stuff matters.

I didn’t fit neatly into a category, but my struggles still screamed ADHD.

Singled out academically, but not for ADHD.

Ironically, my school district assigned me an IEP (Individualized Education Plan) in first grade, right around the time my ADHD started causing issues at school. The IEP had nothing to do with ADHD. It classified my intellectual functioning as “very superior” and laid out a plan to ensure I was appropriately challenged.

A brief note toward the end mentions “some weaknesses in control, appropriate interactions with [my] peers, and tolerance for differences.”

Those “weaknesses” persisted throughout elementary school. I could easily be provoked into verbal or physical outbursts. The other kids, being kids, exploited this. I also blurted out hurtful or annoying comments without thinking. Even setting these issues aside, I struggled to make and keep friends.

Eventually, teachers assumed any problem involving me in their classroom was my fault. They recommended me for a weekly group lunch with the school guidance counselor. I got failing grades on almost every report card, but in one subject only: social attitudes and behavior.

Academic struggles chalked up to motivation

Teachers also noticed academic foibles. I made careless mistakes on my work, forgot to turn in completed homework, and resisted work I didn’t enjoy. One teacher actually described this as me not feeling like focusing.

However, they never pressed the issue. They talked about these things in terms of “effort.” My gifted label probably enabled an assumption I didn’t adequately value or respect the work. Likewise with my social challenges. The word “tolerance” appeared more than once on my reports. It implied I needed to learn to respect others’ input and “work democratically” in groups with varying talents.

That I might’ve been trying my absolute best to apply myself and get along with others, that my behavior was as frustrating and confusing to me as it was to everyone else, didn’t seem to occur to anyone.

Built to coast

I also did okay in school.

I’m a linear, linguistic thinker. My brain is built for multiple-choice tests. I can fake my way through an essay about almost anything.

These qualities masked many of ADHD’s effects on my academic performance. I never learned how to study, but I didn’t need to. I tested well, then immediately forgot most of the information. I got away with leaving papers until the last minute because I wrote (and touch-typed) quickly. When I caught onto concepts easily, or else preferred reading them from the textbook to hearing them in a lecture, I read books or did homework during class.

In other words, I coasted. I got away with undiagnosed ADHD and graduated with a 3.8 GPA thanks to my natural wiring.

Coasting didn’t feel like an achievement

I also graduated feeling like an imposter. My parents and other adults told me I was smart and talented, but praise made me uncomfortable. I’d never worked hard at something I wasn’t good at.

For example, I only took advanced classes in subjects I enjoyed. When I received an invitation to the International Baccalaureate program in seventh grade, I declined because I didn’t feel like doing extra work.

Despite loving field hockey and team sports in general, I didn’t make time to try out after freshman year. One freshman had made the varsity team, and it wasn’t me.

I claimed I quit my private flute lessons to help the family when money was tight, but really I felt uncomfortable receiving exercises I actually had to practice. After that I stuck to groups where I was already among the best players. This wasn’t hard to do. I still had tons of opportunities, but I had the potential to take it so much further.

Throughout my academic career, I accumulated plenty of credits on my resume. I just didn’t feel comfortable calling them achievements. The word implied I’d actually tried hard, or overcome some kind of adversity. All I’d really done was avoid getting found out.

Unprepared for the world — and for long haul ADHD

On the surface, I might’ve looked like I’d learned to succeed with my ADHD. Perhaps even found coping mechanisms to eliminate the need for medication or formal diagnosis.

To that I’d ask, at what cost?

What might my early life have looked like with access to ADHD treatment, including medication and cognitive behavioral therapy? Would I have developed healthier, more secure social relationships? Struggled less with my relationship to food and eating as a teenager? Stayed on the field hockey team? Had enough faith in myself and my perception of reality to leave a toxic relationship? Gone to school for music performance and pursued a life onstage, a life I once believed I needed as much as I needed air?

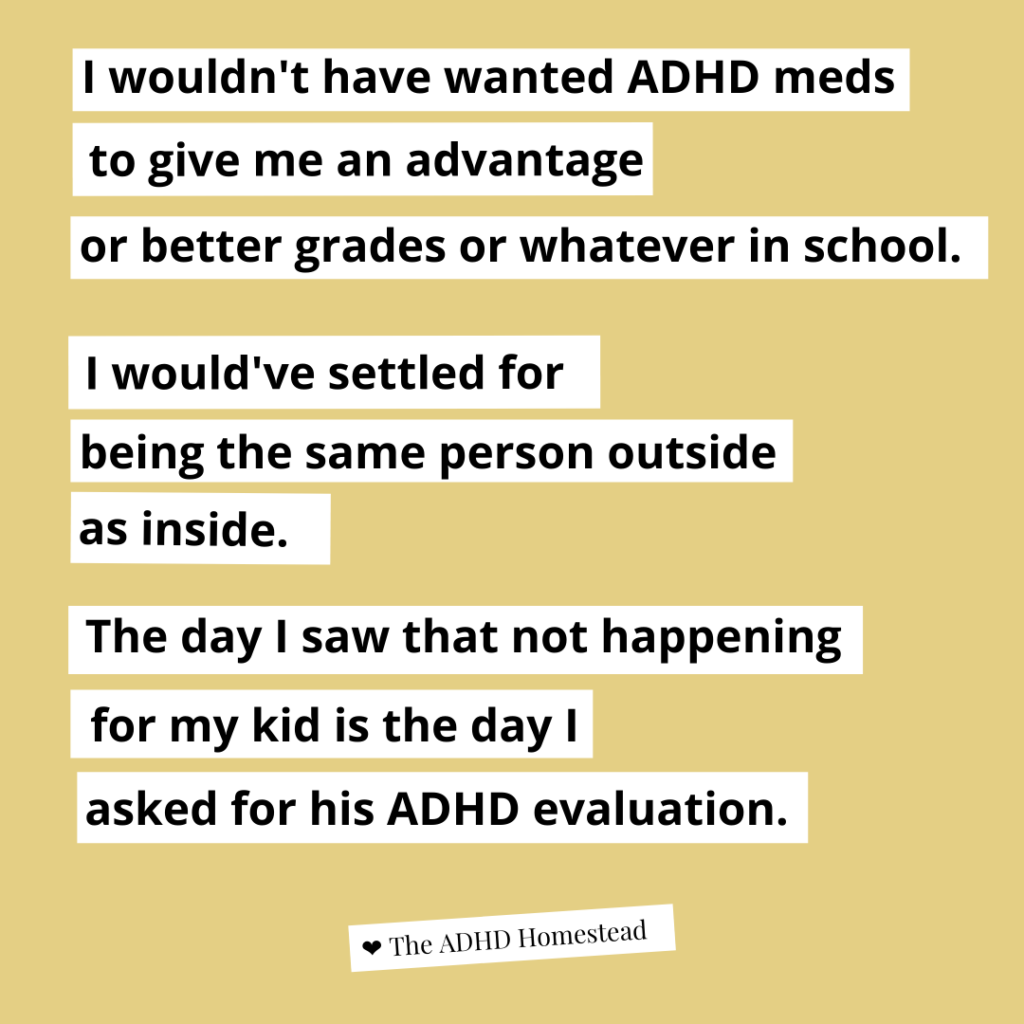

Or maybe just found a way to be truly present in my own life. To weather my own emotional storms. To be the same person on the outside as I was on the inside.

I don’t dwell on this question, but it’s worth asking for the sake of those coming after me. Thirty years later, we still have educators who, even if they feel sure a kid has ADHD, can’t refer them for evaluation unless their grades are suffering.

ADHD is a lot more than that. It’s a lot more than fidgeting, or staring out a window daydreaming. It has defined large parts of my life since at least age six. I know that now, even if no one knew it then. I just wish I could say the same thing would never happen today.

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!