Every once in a while, I have a minor meltdown about my productivity. I’ll seem busy, yet never end the day feeling like I’ve accomplished anything. A couple weeks ago, as summer vacation wound down and our family prepared for the school year, things came to a head again.

I vented to my husband that I was getting nothing done.

He didn’t exactly provide the sympathetic and helpful ear I’d hoped for.

“You’re getting plenty done,” he told me. “It’s just the lower-priority stuff that’s not getting done. You can’t do everything.”

At first I got defensive. How dare he? I told him I felt like my deep creative work was stagnating, and he claimed that’s because it’s “low-priority?”

Upon later reflection, I realized he had a point: I don’t have time to do everything. Therefore, everything I do needs to be a conscious choice.

I had to ask myself: what had me feeling so down about my productivity?

The five harbingers of unproductive work

The root causes of poor productivity follow a common theme for me. Regardless of my actual work output, I feel cruddy about my progress when I don’t choose my progress. That is, when I fail to pause and make intentional choices about what I’m working on and why.

Those decision-making failures fall into five categories:

Lack of a clear goal

In my rush to get to work, I forget to pause and consider what I want to accomplish that day. I start wherever my eye lands first: my email, the tabs I left open from yesterday, or an idea I wrote down when I should’ve been sleeping last night. From there, I wander from task to task however the spirit moves me.

I can spend whole days (or weeks) like this. While I do get things done, I end the day feeling restless and unproductive. I didn’t get to my important, big-picture projects.

A satisfying day begins by getting a clear sense of what I want to work on. Otherwise I stay very busy, but my work feels both pointless and endless.

Failure to decide what to work on

After setting goals for the day’s work, I need to decide what to work on right now. When I complete that block of work time, I need to decide what to work on next.

This sounds obvious, but it’s not. Setting a goal is only the first step. After that come the decisions that make it a reality.

Like the initial goal-setting, all this requires is a pause and an intentional choice. For example, “now I’m going to work on this blog post draft.”

Without that pause, I wander between tasks, usually working on too many of them to make solid progress on anything. I also forget about the goals I set for the day until it’s too late to salvage them.

Multi-tasking

Our brains aren’t made to multi-task. People who claim to be good multi-taskers aren’t really multi-tasking: they’re switching between tasks so fast they think they’re doing everything at once1. Each of these switches has a mental cost that drags down our productivity.

I’m guilty of two different types of multi-tasking: first there’s the indecisive type I described above. Everything open on my desk is important. I don’t know — no, I don’t pause to decide — where to start.

Then there’s what I call impatient multi-tasking. I bet a lot of ADHDers do it. While I wait for [insert slow computer thing here] to finish, I pop open a new browser tab and start another task. Maybe my bank’s website is taking longer than a half-second to log me in. Whatever it is, I can’t possibly waste time waiting for it.

Except now my brain has changed gears. Maybe I forget the first task was even happening. Then, hours later, I stumble across the tab with the bank stuff in it. I notice I’ve been logged out due to inactivity. Shoot — what was I even logging into the bank website for? Now I have to orient myself again. I click Log In, the spinner starts spinning, my ADHD self gets bored, and the cycle repeats.

This is how we get a whole mess of tabs open and too little work actually finished. Instead of reflexively switching to a new app or tab, I try to do something related to what I’m waiting on. I write down a quick note about it, or maybe review my goals or to-do list and decide what I’ll work on after I finish this. It takes practice, but I get a lot more done this way.

Too many distractions/temptations

If this sounds like it requires willpower, you’re right. I have to make a conscious effort not to open that browser tab, switch to that app, or pick up my phone to do a quick check. And humans only have so much willpower2.

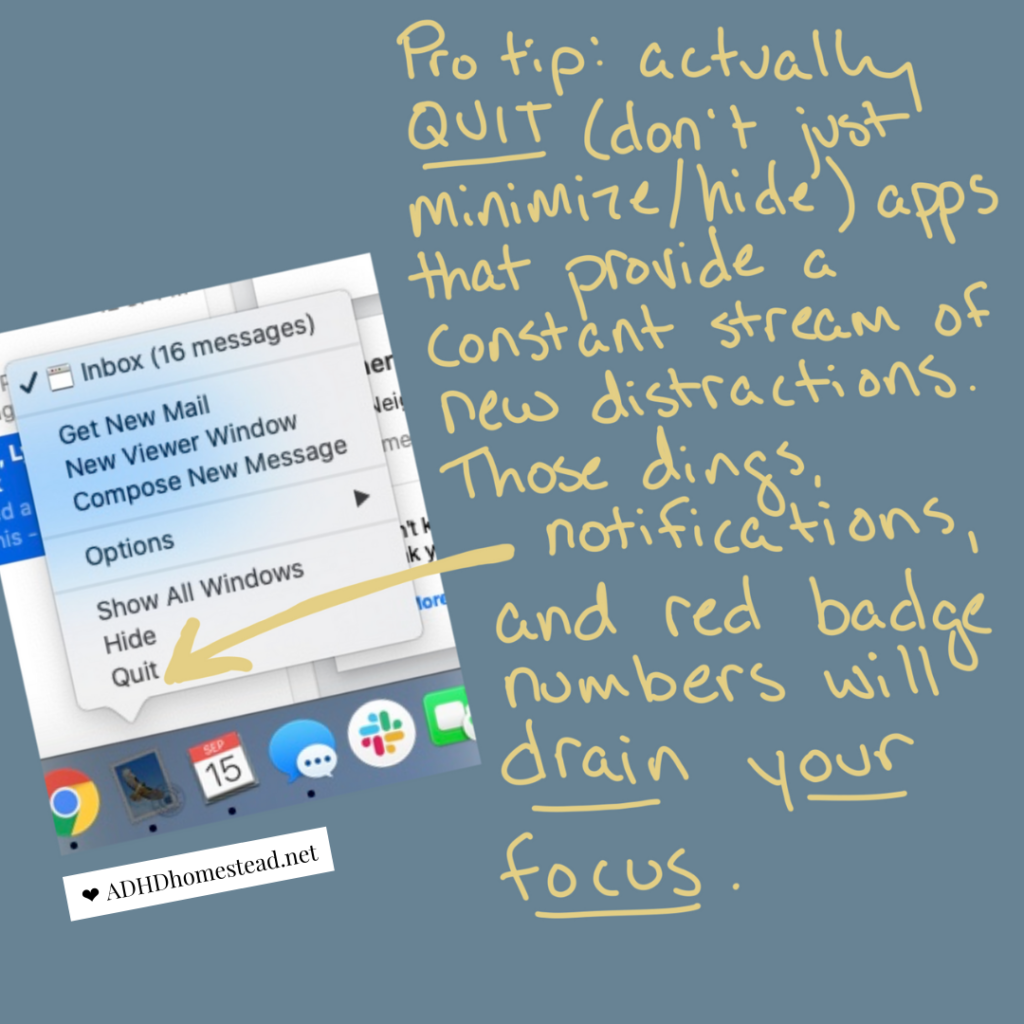

Too many distractions, especially constantly-refreshing streams like email and social media, drain my focus. Truly deciding what to work on — I call it single-tasking — requires me to clear the decks and remove as many temptations as possible.

This means quitting — not just minimizing — my email client to get rid of its badges and notifications, closing all those open browser tabs, and closing any documents not required for the task at hand.

If I’ve gotten myself into an open-tab black hole, this becomes its own task: I go through the tabs one by one and find a way to get them closed, whether it’s by adding a note to my to-do list or saving an article to Instapaper to read later.

This changes the paradigm. Now the act of opening a new app or a new tab sends a signal: we’re changing gears. Instead of having everything open and being able to work on whatever looks interesting, I need to choose to open something new — and decide whether that’s really a good idea.

Trying to push through when I need a break

Single-tasking increases my likelihood of getting into a good hyperfocus flow, or at the very least actually focusing on one thing for long enough to make progress. However, it doesn’t guarantee it. Sometimes I need a break.

Unfortunately, I resist breaks when I feel I haven’t “earned” them yet. I don’t have enough to show for myself, therefore I shouldn’t get a break.

However, I can’t think critically or creatively when I’m hungry. I can’t solve a problem if I’ve stared at it for so long my eyes are about to fall out of my head. Sometimes I’m just burned out.

At these times a walk, a snack, or even ten minutes spent tidying up in another room can dramatically increase my productivity. I’m spending time on the break, but I’d spend more time struggling through the task without one.

My default view of breaks — and I’m sure I’m not alone in this — is toxic and counterproductive. Breaks need to be a key part of my productivity strategy, not just a reward for a job well done.

Pause, decide, focus, repeat.

There are many ways to work frantically all day without making progress on anything that matters. Work time should feel less like whack-a-mole and more like one of those water-gun races. To really engage with a task, it’s important to:

- Identify a single thing to work on

- Clear the decks of anything that will distract from that task

- Spend a decent chunk of time — 20 minutes or more — working on that task without switching over to something different

- When it’s time to switch to a new task, intentionally put this one down — that means closing apps, documents, tabs — and return to Step 1

Sometimes I need a little extra scaffolding to help me do this. In a previous post I talk about how baking sourdough bread or even doing the laundry helps focus my work during the day. It physically enforces a Pomodoro-Method-esque rhythm and reminds me to reflect on my progress at regular intervals.

The effort is worth it. As soon as I rededicated myself to intentional, single-task work habits, my mood completely turned around. I ended my days feeling satisfied and able to engage in restorative down time activities. This doesn’t happen unless I have a feeling of closure about my work day. The actual volume of work done may not have changed, but the quality and nature of it sure did. That made a world of difference.

Footnotes:

1: Since the rise of smartphones, this subject has appeared in lots of popular business and psychology publications. Even so, in 2020 I still see people claiming to be the exception. They’re not, and neither are you. The research is pretty unequivocal on this.

2: The best description of this I’ve found is in Dr. Kelly McGonigal’s book The Willpower Instinct. I highly recommend it!

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!