I intended to write this as a light-hearted post about my childhood report cards. A reader had emailed me to ask about them. They’d seen a few snippets in an old post and wondered: Did I have any more?

I did. I do. That email sent me down kind of a rabbit hole. I looked through my old reports, followed threads, reconstructed the plot lines that led me to the place I eventually ended up.

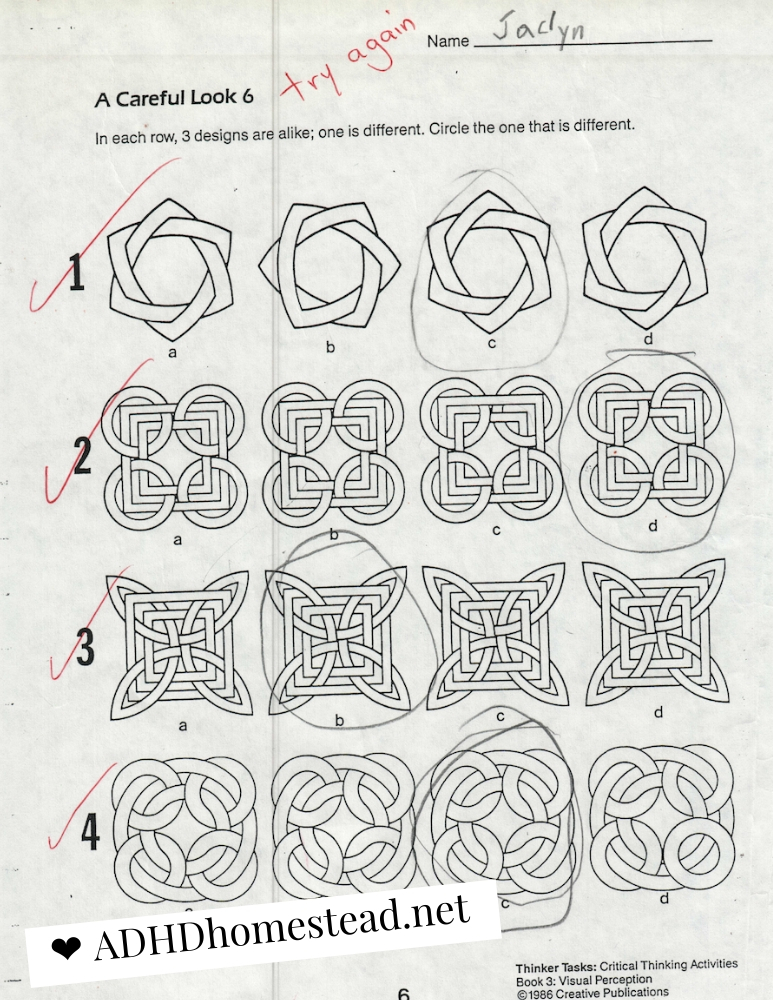

This sort of meander down memory lane used to feel lighthearted. It still can, especially if you look for examples like this pattern recognition assignment from second grade:

I used to explain this away with self-deprecating jokes about how “I’m not a visual thinker.” That may be true, but looking at it now, as I write this at 9:22 a.m. after taking my ADHD meds and going for a thirty-minute walk, I can spot which pattern doesn’t belong. I may not think in pictures, but I can see. Back then I never let my eyes rest on any one image long enough to notice its details.

However, that story about not being a visual thinker carried me pretty far. And it got me thinking about the power in the words we use to describe ourselves, to describe others.

What else did I tell myself?

As I paged through more artifacts of my early academic career — report cards, IEP meeting notes, standardized test scores — I began to question other stories I told myself.

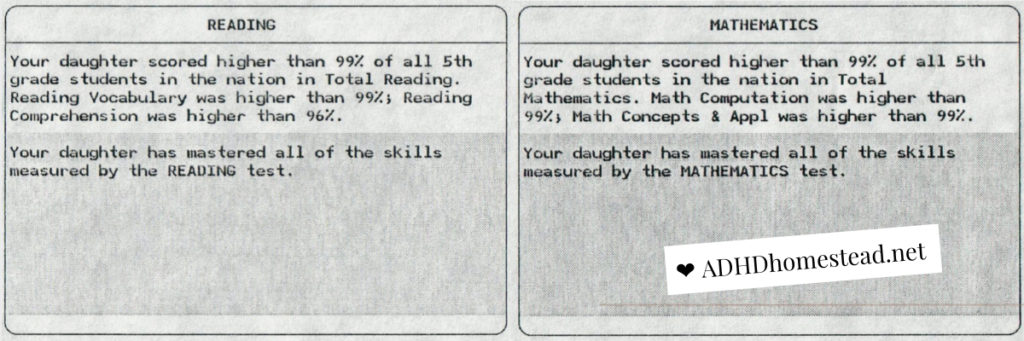

At some point I settled into the idea that I could never excel in mathematics. That I was gifted, but only barely. By high school I loved to make comments about how I “had the lowest IQ they’d let into the gifted program.”

But was any of that true? And if it was, why do these fifth grade assessments claim I exceeded the scores of 98 percent of children my age — including in math?

What stories do we tell our children? Other people’s children?

As we ADHDers get older, we start to believe stories about ourselves. Maybe these stories didn’t feel right at first, but we also struggle to refute them with anything tangible. The stories we absorb from the people around us have the power to sink us or prop us up.

Some stories worked against me, for sure. I avoided anything that required real effort in school but still got good grades, which made me too smart to have ADHD. My ADHD plagued me most in the form of impulsivity, missed social cues, anxiety, and all-consuming emotions that overwhelmed me one minute and vanished the next. This made me selfish, unreliable, rude, oversensitive, melodramatic, aloof.

But I can’t read these stories anymore without asking: what stories didn’t I hear? On more than one occasion, I physically lashed out at my elementary-school classmates. And yet when I clawed someone’s arms bloody for butting in front of me in line during gym class, I was not suspended. I don’t even think I got a detention. Certainly no one decided I’d be lucky just to keep myself out of prison.

After all, I was a white girl from a middle-class nuclear family. Everyone assumed my parents were good, hard-working people doing their best. They assumed I was a bright kid. Labeled me “a delight to teach” despite my foibles. I just needed to work on a few self-control issues.

What do we assume about our potential?

In other words, I had potential. I had the privilege of expectations. My parents worked their butts off at jobs they hoped I wouldn’t have to do when I grew up. They saved their hard-earned money to send me to college. No one, at any point, suggested or even implied I should not or would not get a four-year degree.

ADHDers have serious issues with motivation and self-worth. Years of screw-ups destroy our ability to trust ourselves. That’s why expectations can make or break us. When people looked at me, they assumed a certain potential. A certain trajectory. To break that would’ve required more energy than to go with the flow. Society, or cultural inertia, worked in my favor.

Plenty of kids with ADHD have the same raw intelligence, potential, and worth I did. I can’t shake the question: who gets the benefit of the doubt like I did — and who doesn’t?

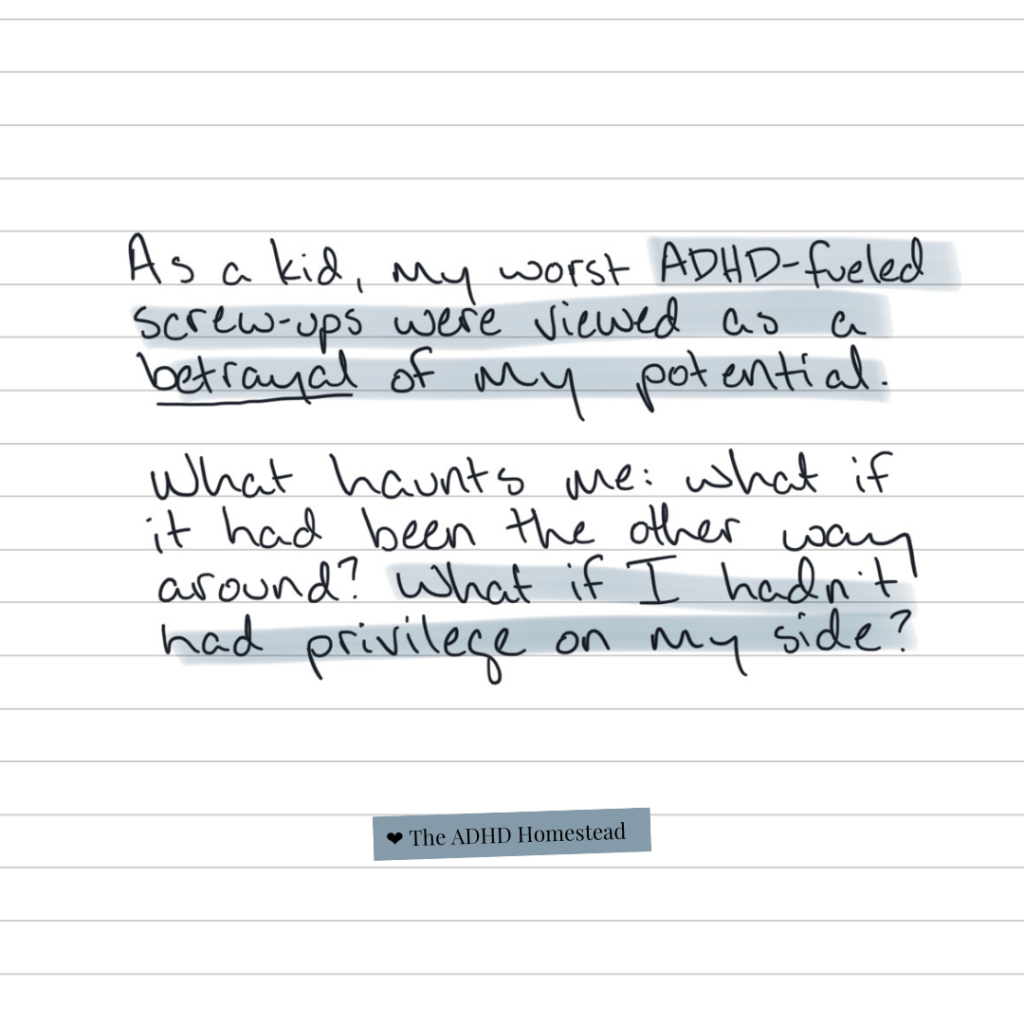

After I attacked that kid in my gym class, my mother sat me down and said, with great disappointment, that I had behaved like an animal. Everyone around me, all the adults with the power to shape my future, viewed this transgression as a betrayal of my potential.

But what if they’d seen it the opposite way around? As an unfortunate fulfillment of my potential? A product of what I was born into? How would my other behaviors look to my teachers, viewed through that lens?

Who gets to call ADHD a gift?

No one viewed me this way, though, and I grew up into the sort of person who could probably choose to call my ADHD a gift if I so desired.

Anyone who calls ADHD a gift speaks from a place of privilege. People have attacked me for saying this. I don’t care. The way the world viewed me as a child was deeply unfair — and when it really mattered, that unfairness tilted in my favor.

This does nothing to diminish my missed diagnosis, the negative labels people did place on me, my loneliness and my anguish and my own squandered potential. Those things still happened. But other things happened too. Assumptions about who I was and what I was capable of, assumptions that ultimately carried me to a life where I could feel safe and comfortable.

This shouldn’t feel comfortable for any of us. Not until every parent can see their love and hard work pay dividends in their child’s future like mine have. I often point to my own struggles as evidence enough why I will never call my ADHD a gift. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. Until every single one of us has the privilege of calling our ADHD a gift if we want to, how can any of us walk around celebrating it? How can any of us take it home as a prize? I want us all to think on that.

I’ll post more report cards later, but after three rounds trying to write that funny, off-the-cuff post today, I decided I needed to say this first.

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!