Many ADHDers struggle to plan, start, and finish projects successfully. The fallout from this haunts every corner of our lives. I’ve written a series of posts about project management and ADHD, using my back garden as an example. This project could’ve created the domestic conflict and neighborhood eyesore so familiar to so many of us. But I’m happy to report it was a success!

The new garden only slightly resembles my original plan, and I may change it in the future. That’s kind of the point. This project reminded me of three big ADHD-friendly project management skills:

- Build in flexibility — and be willing to use it

- Keep individual components of the project separate

- Leave room for the ADHD

Our path may change, and that’s okay

Growing up with unrecognized ADHD, I received a lot of lectures along the lines of, A failure to plan is a plan to fail. Later on, this provided a reasonable-sounding explanation for several disasters I created as a new homeowner. I got too excited to start a project, made a huge mess, and had no idea how to proceed. If only I’d bothered to make a better plan!

That assessment feels misleading now. Yes, we need a plan. However, some ADHDers get so tangled up in the planning, we never start. There are also brain-based reasons to leave room for the ADHD and avoid what I’d call over-planning.

Beware working memory and time perception challenges

Even with medication, my working memory deficits define the way I think. Big projects require attention to many different factors, often all at the same time. I can focus on small parts of a project individually, but my brain can’t pull them all together to consider the whole.

The garden project took my backyard from a rectangle of turf grass bordered by gardens I inherited from a previous owner…

…to a much more organic design. I built a large, curvy, stacked-stone raised bed in the center of the yard with six smaller planting beds scattered around the edges. A flagstone path around the raised bed finished it off.

Creating a plan to produce this exact final product would’ve required experience, research, and attention to detail. That’s a lot to ask of my working memory. It’s hard enough to pay attention to everything from measurements to technique to materials when I know what I’m doing, let alone when I’m learning as I go.

That lack of experience also meant I had no basis to calculate the time and effort it would take to do what I had in mind. ADHDers’ so-called time blindness makes it tough for us to make these estimates even in the best of circumstances.

In other words, any plan I made could easily have been upended by misjudgements and oversights.

Rigid thinking can derail the middle of a project

On top of these perceptual challenges, I’m also a very rigid thinker. Some circles still perpetuate the stereotype that ADHD makes us spontaneous, outside-the-box thinkers. However, anyone can have ADHD. While it may help some of us go with the flow, for others it does the opposite.

If time perception and working memory issues hinder my ability to make a detailed plan in the first place, my rigid thinking turns too much planning into a liability anyway. Once my brain wears a comfortable path in its thinking about something, any deviation — even a good one — can cause a meltdown. Every project has its surprises. Getting too mired in detailed planning sets me up for failure.

Get something (anything) up and running as soon as possible

I struggled with this balance between over- and under-planning for years. I finally started to get the hang of it when I became an app developer. Good software development leaves plenty of room for on-the-ground learning and refinements. You can plan all day, but nothing beats the lessons you learn from watching your work in action.

This makes it essential to figure out what your minimum viable product actually is: what is the absolute least I could do to get something useful up and running? What’s the cheapest, most efficient way to test out this idea?

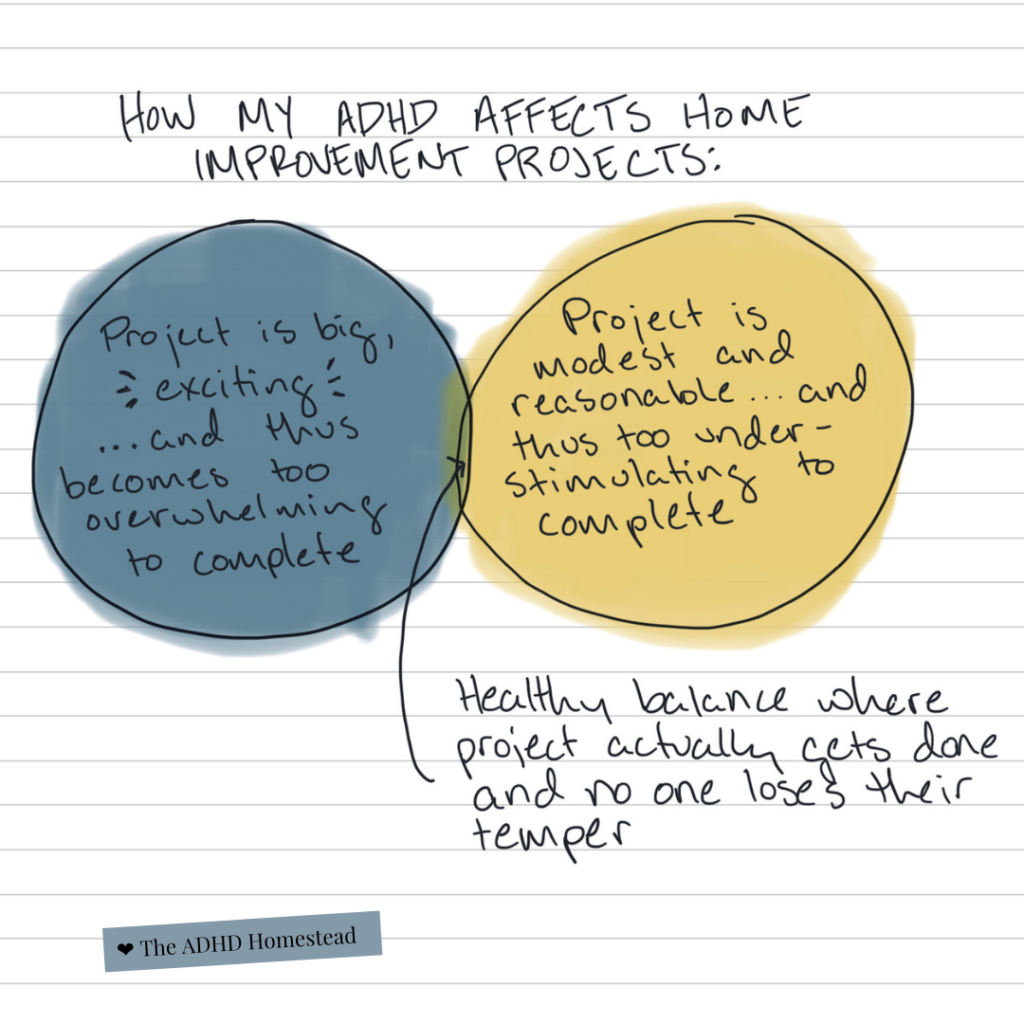

My brand of ADHD doesn’t lend itself naturally to this. I want something big and showy. I don’t want to settle. My brain craves the huge gratification, the rush of dopamine.

This leads me down a path of too-big projects. I try to cram everything I’ve ever wanted into my initial plan, only to get jammed up on the first roadblock.

This time I scrapped anything that would make the plan too complicated — or introduce a new, separate-yet-codependent project to the mix. I resisted the urge to combine my turf grass reduction/garden building project with any of the following: pergola-style hammock stand with trellised hops vines, new deck attached to the back of the house, any permanently-installed hammock stand, custom-built trellises, or a fire pit. Those can come later — if I still want them.

Not only did creating a minimum viable backyard garden help me celebrate sooner, it allowed me to learn from the process and refine my plans as necessary. When the unexpected happened, I had room to adjust rather than getting derailed.

Build in flexibility and room for error re-assessment

That flexibility is key. My working memory is the worst enemy of my attention to detail. No matter how hard I try, I always miss something. There’s always a surprise: something I forgot to consider, or pieces that don’t fit together as expected.

I need to plan for this. If I know I won’t grasp the details effectively until I start working, why not accommodate that instead of trying to force my brain to lean on its weak spots?

I considered many options for building my garden beds, from traditional raised wood beds to stock tanks to — my personal favorite — salvaged corrugated steel with wood trim. However, these all felt too permanent. I’d have to trust my initial sketches and measurements absolutely. Once I bought materials and built the beds, I couldn’t easily reconfigure.

I ended up choosing stacked fieldstone as my building material. It referenced pre-existing materials (our house has a stone foundation), but more importantly, it could change shape. The stones weren’t cut to size or permanently attached to one another. If I wanted something different, I could unstack and restack. I could finalize the shape of my garden beds on the fly.

Before ordering my stone, I used bricks to map out a few ideas and photographed the layouts I liked best. This helped me think through a few ideas, but my final design looked unlike any of my initial plans. I hadn’t accounted for the larger size of the stones. The smaller shapes and tighter curves I’d imagined wouldn’t work. Fortunately, it didn’t matter! I built what I could with what I had, and it turned out fine.

Everything is case by case

Not every project can go like this. Some, like the major kitchen renovation we did several years ago, require comprehensive plans and precise measurements up front. Before we started that project, I thought carefully about the reality of our skills, our free time, and our ADHD — and I outsourced it.

In my book Order from Chaos, I spend a lot of time talking about our ADHD reality. My reality is, the kitchen was not the DIY project for me. If I wanted it to turn out well and take weeks rather than years, I needed to wait until I’d saved enough money to pay a designer to manage it.

However, some projects can be tuned to work with, not against, our ADHD. I gave up some of my high-impact, dopamine-feeding ideas for the backyard in favor of a plan that could flex as I went. This meant even when I encountered the unexpected — a place where my brain hadn’t been able to hold all the factors I needed to consider — I could quickly adapt and continue working.

And I was rewarded with an even better dopamine rush at the end: I actually finished the project! It’s open-ended, there’s room for improvement, but it’s done enough to celebrate and not feel ashamed every time I look at it. In my ADHD world, that feeling means more than our neurotypical friends will ever know.

Hey there! Are you enjoying The ADHD Homestead?

Here's the thing: I don't like ads. I don't want to sell your attention to an advertising service run by the world's biggest data mining company. I also value my integrity and my readers' trust above all, which means I accept very few sponsorships/partnerships.

So I'm asking for your support directly. For the cost of one cup of coffee, you can help keep this site unbiased and ad-free.

Below you will find two buttons. The first lets you join our crew of Patreon pals and pledge monthly support for my work. Patrons also have access to my Audioblogs podcast. The second takes you to a simple donation page to pledge one-time or recurring support for The ADHD Homestead, no frills, no strings. Do whichever feels best for you!